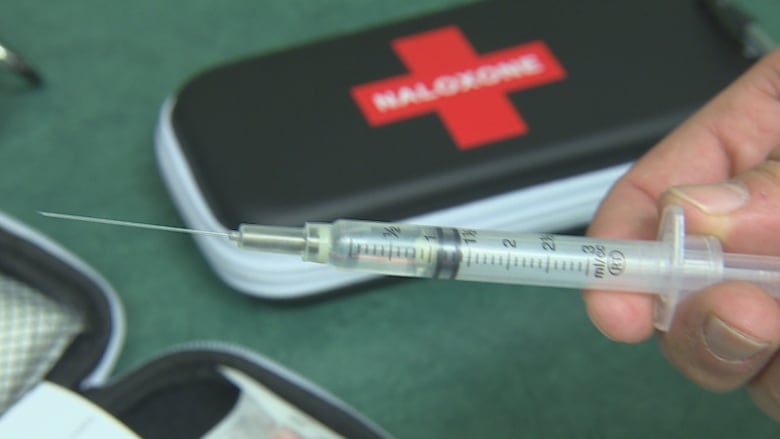

Edmonton councillors think more city workers should carry naloxone

Edmonton firefighters have administered naloxone 31 times since February

Some Edmonton councillors are questioning why city workers likely to come into contact with people overdosing on opioids aren't equipped with the antidote.

A report released Thursday giving an opioid crisis update says bylaw officers, peace officers, park rangers and recreation centre staff are "likely to encounter a person in distress or unconscious from possible opioid misuse," but doesn't recommend training them to carry and administer naloxone.

Coun. Michael Walters said that's a gap identified in the report.

I think it is necessary that we provide more people with those tools.- Coun. Michael Walters

"I think it is necessary that we provide more people with those tools," said Walters.

He said while walking recently in the river valley with a street outreach team he saw people injecting drugs, and used needles on the ground.

"It's all over the place and our park rangers and our police officers and our firefighters and our first responders and our social agency staff are exposed," Walters said. "Those resources, those kits, need to be made available in my view."

'A first line of defence'

Coun. Bev Esslinger wants to know why Edmonton isn't doing something similar.

She said equipping park rangers would be "a first line of defence," but there needs to be discussion about which other workers should carry and be trained to administer the antidote.

In the past year, more than 170 people died from opioid overdose in Edmonton; about 70 per cent of those fatalities occurred outside of the inner city.

Since February, firefighters have administered naloxone 31 times.

Long-term thinking

The report looks at what more Edmonton can do. The city is working to create safe-injection sites, enhance information-sharing among agencies and educating employees.

Walters said Edmonton is still reacting to the crisis, but really needs to think long-term. He's hopeful the provincial commission announced this week to try to deal with the rising death toll from opioid overdoses will make some headway.

- INTERACTIVE: How Alberta's fentanyl crisis escalated despite years of warnings

- 'Our aim ... is to keep people alive': Alberta invests $30M to deal with opioid crisis

"I think we have to continue to press for bigger, long-term, root-cause thinking: How do we turn off the tap of addiction and when people do get addicted, how do we get them treatment?" Walters said.

Esslinger, like Walters, said municipal, provincial and federal governments are all going in the right direction and need to keep working together.

"The sooner you get help to people who are overdosing, the better off they are," she said.