Are we really headed to the moon?

There have been plans for decades to head back to celestial neighbour

Although the plan hatched by NASA and its Russian counterpart to build a space station near the moon seems like a solid launching pad for further human space exploration, it's a message that's been heard before.

On Wednesday, the U.S. agency and Roscosmos announced they are working on a partnership to build the station, called the Deep Space Gateway.

The statement, made at the 2017 International Astronautical Congress in Sydney, Australia, is the next step in a space program that's largely been on hold for the Americans.

The last time humans were on the moon was in 1972. Aside from the International Space Station, there haven't been any solid plans of further human space exploration.

- U.S., Russia to collaborate on spaceport orbiting moon

- Scientists find new evidence of water in the moon

- SpaceX to fly 2 people around the moon by next year

Randy Attwood, a space historian and executive director of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, said there have been plans to visit the moon for decades, but nothing that seems to be long-term. And, without funding, it lacks teeth.

"These organizations are having trouble finding some sort of plan and not only sticking to it, but also getting funding for it," Attwood told CBC News.

"My concern about this Gateway is that it's not an announcement that we got funding," he said.

"How many times have we said we're going to go to the moon?"

The United States has set out visions to explore space for decades. The challenge is changing governments: each new administration has a new agenda and space may not be on the top of its list. So each time, the goal post moves.

For example, in 2004, President George W. Bush presented a speech on humans exploring the cosmos.

"Our ... goal is to return to the moon by 2020, as the launching point for missions beyond," he said. "Beginning no later than 2008, we will send a series of robotic missions to the lunar surface to research and prepare for future human exploration."

Except there haven't been any robotic missions to the moon — by Americans, at least. China sent a rover, Yutu, to the moon in 2013. And it's highly unlikely that the moon will see humans by 2020.

Fast forward to 2010 and President Barack Obama's budget for the next year scrapped NASA's Constellation program that would send humans back to the moon.

However, out of that came the Orion spacecraft that NASA touted would be the vehicle — launched on a new Space Launch System, already behind schedule — that would take humans to Mars. Orion's first unmanned test launch on a Delta IV rocket was a success in December 2014.

'Makes sense'

So now the vision is to head to the moon first. Some may argue that it's a more desirable location for a few reasons, particularly its proximity.

However, Wednesday's announcement doesn't say that humans will be returning to the moon. It's about putting a station nearby, in an orbit between Earth and the moon — called a cislunar orbit — as a spot from which a spacecraft, such as Orion, could head to the moon or beyond.

Even NASA acknowledges the announcement was simply a plan of co-operation.

"While the deep space gateway is still in concept formulation, NASA is pleased to see growing international interest in moving into cislunar space as the next step for advancing human space exploration," Robert Lightfoot, NASA's acting administrator at its headquarters, said in a statement Wednesday.

Why it took so long to get here is unbelievable.- Randy Attwood

Cheryl Warner, a NASA spokesperson. told CBC News, "This is a really early concept."

Back during the Apollo missions, the drive was to get to the moon ahead of the Soviet Union. With no space race, there's not as much drive to explore outward. International collaboration is a way Americans can avoid the burden of the cost. It's the same way the space station came to be an international joint effort.

"Having to include multiple countries in this makes sense," Attwood said. "And having some sort of lunar space station makes sense as well. Why it took so long to get here is unbelievable."

Canada's involvement

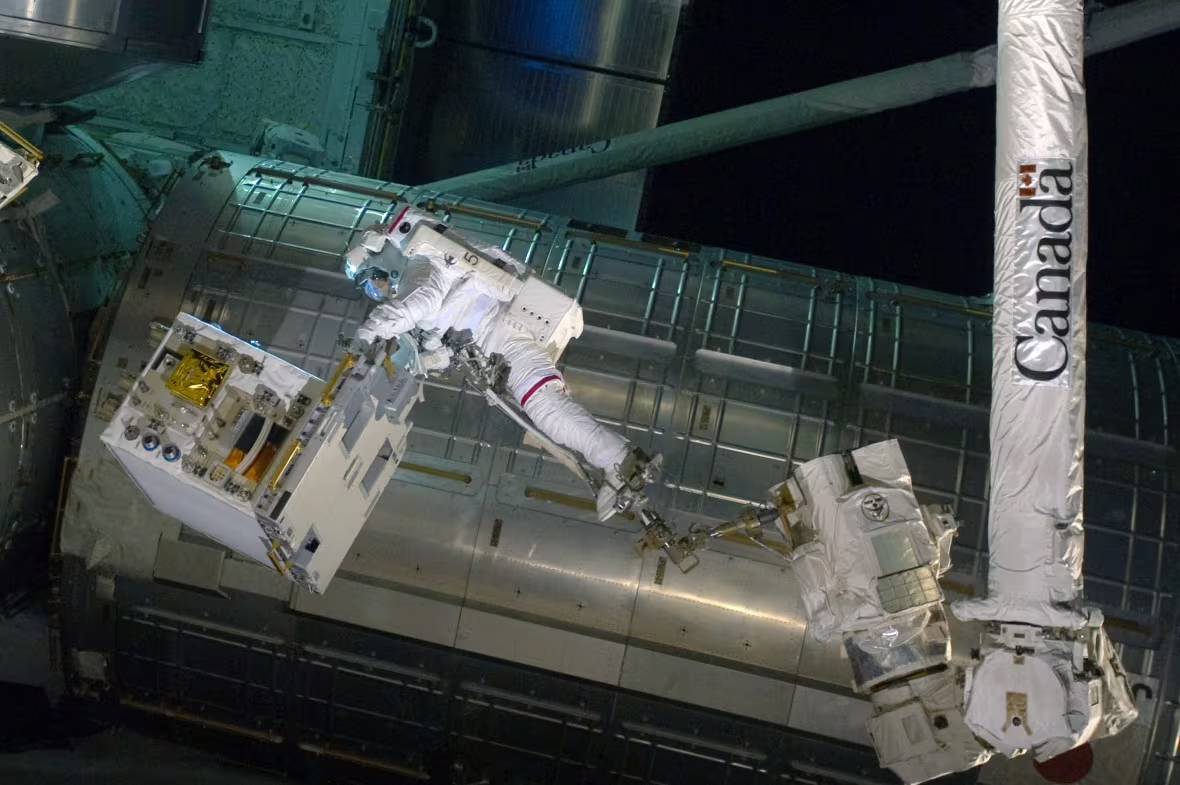

Although not part of the announcement, the Canadian Space Agency has its sights set on the moon as well.

In August, it awarded MacDonald, Dettwiler and Associates — maker of the Canadarm — a $2.5-million contract to build a "deep-space robotics system, which could be used to operate and maintain a future space station near the moon."

While some may question why humans need to explore space in the first place, Attwood said it's human nature.

"There is this desire to explore. And it's always been there. If there's any way for someone to look over the next mountain or hill or whatever, there's always someone who's willing to do that," he said.

"I think people in general are explorers."